This is the fifth post in a five-part series where we'll give you a look inside this important new COVID-19 resource. In case you missed it, we recommend viewing the series in order, starting with Part One.

This is the fifth post in a five-part series where we'll give you a look inside this important new COVID-19 resource. In case you missed it, we recommend viewing the series in order, starting with Part One.

As an EMS provider, staying safe through the evolving COVID-19 situation involves distinct challenges. That's why the Public Safety Group, in partnership with the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, is pleased to introduce Evolution of EMS: COVID-19 Guidance for EMS Providers. This unique resource offers strategies and insights designed specifically for you.

This excerpt looks at the profound impact COVID-19 has had on health care systems around the world and the public health implications affecting EMS providers.

Evolution of EMS: COVID-19 Guidance for EMS Providers describes the SARS-CoV-2 virus and disease, prevention tactics, vaccine development, treatment, and public health implications, particularly as they affect providers working in the field. It’s not designed to supply everything you need to know about COVID-19, but rather to brief you on key issues and considerations. COVID-19 Guidance for EMS Providers also offers references for learning more and staying up to date. The goal: empowering you to protect yourself, your co-workers, and those you serve more efficiently and effectively.

There are three easy ways to access COVID-19 Guidance for EMS Providers:

- Read Excerpts on the Public Safety Group Blog:

All five excerpts have been rolled out on our Public Safety Group blog, free of charge (Part One is available here, Part Two is available here, Part Three is available here, Part Four is available here, and Part Five is available below)

- Sign Up to Receive a Free, Complete Copy of the Resource:

Visit http://go.psglearning.com/COVIDGuidanceNow to request your free copy today. We'll email you a PDF to download as soon as the complete resource is available later this Fall:

I Want to Request My Free PDF:

COVID-19 Guidance for EMS Providers

- Purchase Physical Copies of the Resource on our Website:

Visit http://go.psglearning.com/COVIDGuidance to pre-order your physical copy which will be available later this Fall

Questions? Please contact your dedicated Public Safety Specialist today.

Part Five: Public Health Implications

COVID-19 has had a profound impact on health care systems around the world. For EMS providers, the public health implications affect everything from patient interactions and transportation decisions to the basic operation of EMS stations and agencies.

Public Safety and EMS

For EMS providers, adhering to standard recommendations relating to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, such as physical distancing and environmental disinfection, can be extremely challenging. It is recommended that you attempt to maintain a distance of at least 6 feet from others whenever possible, when on duty and off. In addition, discourage large groups from gathering on scene, and limit extra riders in the EMS vehicle whenever possible. Similarly, limiting the number of EMS personnel and other responders on scene or in any crowded or tight spaces can help reduce potential exposures.

Numerous studies have demonstrated the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus via both droplets and physical contact. Airborne transmission, particularly in indoor settings with poor ventilation, is an increased concern when people congregate indoors due to cooler weather. Models suggest the potential for airborne virus transmission at distances up to 8 meters (approximately 26 to 27 feet), well beyond the current distance recommended for social distancing (Klompas et al. 2020). Additionally, there is increasing concern that airborne virus spread occurs even in the absence of known aerosol-generating procedures, such as intubation, forceful coughing, bag-mask ventilation, and nebulizer therapy (Wilson et al. 2020). Physical activities requiring heavy breathing, such as singing and exercising, have been linked to increased airborne virus transmission.

Many EMS and first responder activities inherently require very limited distance between provider and patients, colleagues and coworkers, or the general public. A large portion of these activities require direct physical contact. In addition, EMS providers may be more vulnerable to airborne transmissions emitted during procedures such as open suctioning of airways and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Approximately 6 months into the COVID-19 pandemic, a small study found the fatality rate for COVID-19 per 100,000 people to be almost 50% higher for EMS providers than for the general population, at 91 per 100,000 versus 62 per 100,000, respectively (Maguire et al. 2020). Therefore, proper use of the correct PPE is absolutely essential.

Specific precautions and protocols for EMS providers will vary by agency. These measures are crucial to limit transmission risk to providers and the community. They may include changes in patient assessments, efforts to diminish aerosols, and practices to limit the duration or intensity of EMS provider exposure.

An example of a revised practice intended to prevent the transmission of COVID-19 is the use of metered dose inhalers instead of nebulized medications for certain respiratory emergencies. Nebulizers aerosolize medications and are thought to also aerosolize virus particles, releasing them into the environment. If nebulized medications must be used, many organizations advise attempting to administer them in a negative pressure environment, using a nebulizer mask instead of a T-piece and covering it with a surgical/procedural mask. Providers are also advised to perform these procedures on scene whenever possible, avoiding their use in the back of a confined ambulance (Indiana Department of Homeland Security 2020).

The American Heart Association (AHA) has released revised guidelines for resuscitation of patients who have or are suspected of having COVID-19. These guidelines include the use of filters and a tight seal during bag-mask ventilations. The CDC, AHA, and others advocate for a HEPA-rated filter on bag-mask devices and ventilators to avoid releasing contaminated exhaled ventilation into the environment. Other strategies include use of supra-glottic or extraglottic airway devices in lieu of endotracheal intubation, when possible, or having the most experienced provider perform airway procedures to minimize the duration of exposure.

CPAP, PPV, and other respiratory interventions have been shown to produce aerosolized virus particles. EMS providers can expect their organizations to provide guidelines for N95 respirator use and other protective measures applied during these procedures. A variety of sources are also recommending the use of a surgical/procedural mask over an oxygen delivery device, including nonrebreather masks and high-flow nasal cannulas.

All of these new procedures and guidelines are intended to protect EMS providers and others from exposure to COVID-19. As new research is performed and new lessons are learned, these procedures and guidelines will continue to evolve.

Supporting Testing and Contact Tracing

Testing people for infection with SARS-CoV-2 fulfills a number of public health obligations. A symptomatic person who tests positive may benefit from a number of medications or treatment strategies that may not be indicated for other infectious causes; such strategies include specific antiviral medications, corticosteroids, and other treatment adjuncts (Corum et al. 2020). Infection and antibody test results provide an important perspective when making clinical decisions, such as the following:

- Determining clinical treatment strategies

- Assessing the need for isolation precautions

- Determining the necessary PPE

- Considering cohorting patients (keeping those with the same medical condition closer together)

Test results will also affect whether infected people need to isolate or quarantine to protect others. As defined by the CDC, isolation refers to people staying away from others when they are infected; quarantine refers to people staying away from others when they might be infected.

The CDC recommends a variety of indications and timelines for people with COVID-19 to avoid close contacts, return to work, and receive elective medical care. Given the risk of false-negative results, people with high-risk exposures, travel, or suspicious symptoms may still need to endure a prolonged quarantine to minimize the risk of inadvertently spreading the virus to others despite early negative test results after initial exposure (Figure 5-2).

Figure 5-2: Representative isolation and quarantine guidance.

Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Accessed September 10, 2020.

Aggregated test results become extremely important when monitoring the spread or containment of the overall pandemic. Public health, government, and private sector leaders use these data and other key indicators to guide an array of decisions impacting every facet of public life, including the implementation or relaxation of public health orders, the allocation of scarce resources such as PPE or health care personnel, and patient distribution.

Key test-based indicators used to monitor the status of the pandemic include the following:

- Raw total of positive cases

- Positive tests per fixed population (often per 100,000 or 1 million overall population)

- Test positivity rates

- Demographic distribution

Public health officials use a strategy known as contact tracing to slow the spread of COVID-19, as well as other infectious diseases. Contact tracing involves identifying a person who tests positive for the SARS-CoV-2 virus and then identifying other people who have been in contact with that person. Those who have been in contact with the infected person are instructed to monitor for symptoms and quarantine until an adequate amount of time has passed without symptoms (Figure 5-3).

Figure 5-3: CDC contact tracing guidelines.

Reproduced from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Contact Tracing for COVID-19. Accessed September 10, 2020.

*If contact tests positive or develops COVID-19 symptoms, case investigation is necessary.

Safety Within Congregate Settings

COVID-19 has widely proliferated through many congregate living facilities such as skilled nursing facilities, prisons, and homeless shelters. These facilities face many unique challenges in preventing disease transmission. EMS providers who work in or respond to these settings frequently encounter facilities with PPE shortages, inadequate staffing, rapid transmission of COVID-19 among residents, barriers to prompt virus testing, and additional introduction of infections through staff or visitors.

Health care providers in these settings must carefully balance the risk of personal exposure against the risk of patient cross-contamination, often while working with an extremely limited supply of PPE. The surge in cases, combined with massive demand for PPE amid severe supply chain disruptions, has forced many health care facilities and other congregate living facilities to employ novel practices to protect staff.

Early in the pandemic, when N95 filtering face piece respirators had grown scarce, the CDC and other regulatory agencies provided guidance on extended use, limited reuse, and reprocessing (sometimes referred to as resterilization) of N95 respirators (Figure 5-4). These approaches allow single-use, disposable N95 respirators to be used for multiple patients or multiple wearers, often spanning days, weeks, or longer.

Figure 5-4: Resterilizing N95 masks.

© Nor Gal/Shutterstock.

Extended use refers to leaving a mask on through multiple encounters with different patients who are either infected or potentially infected, without removing the mask between encounters. Reuse refers to removing the mask between encounters but using the same mask for multiple patient encounters. Reuse of masks is discouraged when an organism can be spread by contact (fomite) transmission, as the potential for exposure is much higher with repeated donning and doffing.

The FDA has approved a process that uses heated, pressurized hydrogen peroxide to disinfect used N-95 respirators without degrading the filter materials for a limited number of times. This system allows for repeated use of the same respirator by multiple wearers without the risk of infectious material remaining on the respirator from one wearer to the next.

EMS and other health care providers working in congregate living facilities may use a combination of single-use disposable PPE and other reuse, extended-use, or reprocessed PPE. A common approach is for the EMS or health care provider to wear the same face piece during the entire work shift, while changing disposable gowns and examination gloves between each patient encounter.

During any PPE removal, it is essential that wearers not contaminate themselves and risk exposure. Many PPE removal procedures require an assistant to safely remove contaminated PPE. Follow your agency’s or facility’s guidelines, or refer to a reliable source, such as the CDC, for generic instructions for different types of PPE.

Safety in Crew Quarters and Fire Stations

EMS providers in many areas may live in a congregate setting such as a firehouse or EMS station for many consecutive days while on prolonged duty. In this setting, where workers may be seeking rest or a break in a communal area, physical distancing practices can be difficult to follow; however, precautions must be maintained. Consider that each EMS provider, firefighter, or other first responder is at an increased risk for active COVID-19 infection, as discussed previously. These high-risk providers are now cloistered together, where any single provider can infect countless others. Thus, not only might staffing needs in this vital profession be compromised, but the very professionals charged with safeguarding the public might instead spread the disease to high-risk patients.

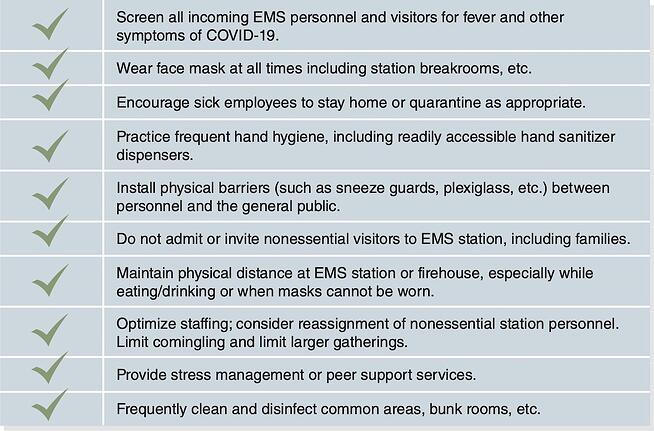

An alarming number of COVID-19 clusters have developed in fire stations around the United States, prompting specific guidance from the CDC, the US Fire Administration, and various other agencies. Some key recommendations for EMS providers and firefighters living in congregate settings during COVID-19 have emerged (Table 5-1).

Table 5-1: EMS Recommendations for Congregate Living Settings

Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Interim Recommendations for Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Systems and 911 Public Safety Answering Points/Emergency Communication Centers (PSAP/ECCs) in the United States During the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Accessed November 6, 2020; United States Fire Administration (USFA). 2020. Information for First Responders on Maintaining Operational Capabilities During a Pandemic. Accessed November 6, 2020.

Coping With Health Care Capacity Demands

The massive spread of COVID-19 has pushed many states, regions, and health systems to increase hospital and health care system capacity. EMS providers may see new temporary field hospitals opening as the pandemic continues. The US military has opened at least 17 additional temporary hospital sites, although many have had limited patient care activity. Many other state-based National Guard units have been deployed to a wide variety of COVID-related activities to support field hospitals, health care facilities, and other congregate settings. Hospitals throughout the country have implemented surge plans to increase overall hospital or ICU capacity, including the use of alternate care sites.

As regions or individual hospitals experience a patient surge, they often cancel elective appointments and surgeries to preserve PPE and other resources. They also reposition staff to optimize patient care capabilities when a high patient volume and acuity are present.

All of these efforts have the potential to affect transportation destination choices for EMS providers. EMS providers performing both prehospital and interfacility patient transports may experience frequent changes in sending or receiving facilities as alternate care sites or inpatient departments are created, expanded, or relocated due to COVID-19. As transport destination changes continue to occur, EMS providers should expect additional guidelines, protocols, or instructions regarding receiving facilities for patients suspected of having COVID-19.

Home Quarantine for EMS Providers

EMS providers may be instructed to isolate or quarantine at home after testing positive for COVID-19, having a high-risk exposure, or engaging in an activity that creates the risk of virus transmission. EMS regulatory departments and individual EMS agencies may have specific protocols for personnel to follow while under isolation or quarantine (Table 5-2).

Table 5-2: Recommended Leave at Home Protocols

Adapted from Whatcom County, Washington, Emergency Medical Services. 2020. Leave at Home Instructions. October 12, 2020.

Maintaining Perspective: Now and in the Future

COVID-19 has dramatically changed many facets of public life, including the ways in which EMS providers interact with patients, each other, and their workplace. It is impossible to predict how long these changes will last, or what practices will remain indefinitely. It is certainly possible that the COVID-19 pandemic will make certain public health measures, such as wearing a mask, a permanent part of our lives, just as mask wearing has become routine in parts of eastern Asia.

The public health implications of this pandemic will continue to have a significant impact on the EMS profession. As professionals on the front lines, it is vital to follow recommended guidelines and protocols, approach each interaction with care, and stay informed of both agency and public health recommendations as the situation continues to evolve.

References

All Things Considered. US field hospitals stand down, most without treating any COVID-19 patients. National Public Radio. https://www .npr.org/2020/05/07/851712311/u-s-field-hospitals-stand-down-most-without-treating-any-covid-19-patients. May 7, 2020. Accessed October 13, 2020.

BLS healthcare provider adult cardiac arrest algorithm for suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients. American Heart Association web-site. https://cpr.heart.org/-/media/cpr-files/resources/covid-19-resources-for-cpr-training/english/algorithmbls_adult_cacovid _200406.pdf?la=en. Updated April 2020. Accessed October 13, 2020.

American Hospital Association. Coronavirus update: Technology for the decontamination and reuse of N95 respirators now available. https://www.aha.org/advisory/2020-04-08-coronavirus-update-technology-decontamination-and-reuse-n95-respirators-now. Accessed October 13, 2020.

Pandemic planning. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hcwcontrols/recommended guidanceextuse.html. Updated March 27, 2020. Accessed October 13, 2020.

Interim recommendations for Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Systems and 911 Public Safety Answering Points/Emergency Communication Centers (PSAP/ECCs) in the United States during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-for-ems.html. Updated July 15, 2020. Accessed October 12, 2020.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical questions about COVID-19: Questions and answers. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/faq.html# Infection-Control. Updated August 4, 2020. Accessed October 13, 2020.

When to quarantine. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov /coronavirus/2019-ncov/if-you-are-sick/quarantine.html ?CDC_AA _refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fif-you-are-sick%2 Fquarantine-isolation.html. Updated September 10, 2020. Accessed October 13, 2020.

How to protect yourself and others. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www .cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention .html. Updated September 11, 2020. Accessed October 13, 2020.

COVID view: A weekly surveillance summary of US COVID-19 activity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www .cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covidview/index.html. Updated October 9, 2020. Accessed October 13, 2020.

Corum J, Wu KJ, Zimmer C: Coronavirus drug and treatment tracker. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/science/coronavirus-drugs-treatments.html. Updated October 4, 2020. Accessed October 13, 2020.

Indiana Department of Homeland Security. Indiana Department of Homeland Security COVID-19 EMS Manual. https://www.in.gov/dhs/files/IDHS-COVID-19-Manual-04162020.pdf. Accessed October 13, 2020.

Johns Hopkins University of Medicine. Daily state-by-state testing trends. https://

coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/individual-states. Accessed October 13, 2020.

Klompas M, Baker MA, Rhee C: Airborne transmission of SARSCoV-2: Theoretical considerations and available evidence. JAMA 2020;324(5):441-442.

Li J, Fink JB, Ehrmann S: High-flow nasal cannula for COVID-19 patients: Low risk of bio-aerosol dispersion. Eur Respir J 2020;55(5):2000892.

Maguire BJ, O’Neill BJ, Phelps S, Maniscalco PM, Gerard DR, Handal KA: COVID-19 fatalities among EMS clinicians. EMS1. https://www.ems1.com/ems-products/personal-protective-equipment-ppe/articles/covid-19-fatalities-among-ems-clinicians-BMzHbuegIn1xNLrP/. Accessed October 13, 2020.

Setti L, Passarini F, De Gennaro G, et al: Airborne transmission route of COVID-19: Why 2 meters/6 feet of inter-personal distance could not be enough. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17(8):2932.

Wilson N, Corbett S, Tovey E: Airborne transmission of COVID-19. The British Medical Journal. https://www.bmj.com/content/370/bmj .m3206. Accessed October 6, 2020.

Yuen K-S, Ye Z-W, Fung S-Y, Chan C-P, Jin D-Y: SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: The most important research questions. Cell Biosci 2020;10(40).

3d3bb467-e9ed-4611-87cd-e46c025ac32b.webp?sfvrsn=a1b7a841_3)